Split-radix FFT algorithm: Difference between revisions

en>Giftlite m →Split-radix decomposition: mv . |

en>Gryzzly92 No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

The '''Ramberg–Osgood equation''' was created to describe the non linear relationship between [[Stress (physics)|stress]] and [[Strain (materials science)|strain]]—that is, the [[stress–strain curve]]—in materials near their [[Yield (engineering)|yield points]]. It is especially useful for metals that ''harden'' with plastic deformation (see [[work hardening|strain hardening]]), showing a ''smooth'' elastic-plastic transition. | |||

In its original form, the equation for strain (deformation) is<ref name=paper>Ramberg, W., & Osgood, W. R. (1943). Description of stress-strain curves by three parameters. ''Technical Note No. 902'', National Advisory Committee For Aeronautics, Washington DC. [http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19930081614_1993081614.pdf]</ref> | |||

::: <math>\epsilon = \frac{\sigma}{E} + K \left(\frac{\sigma}{E} \right)^n</math> | |||

where | |||

: <math>\epsilon</math> is [[Strain (materials science)|strain]], | |||

: <math>\sigma</math> is [[Stress (physics)|stress]], | |||

: <math>E</math> is [[Young's modulus]], and | |||

: <math>K</math> and <math>n</math> are constants that depend on the material being considered. | |||

The first term on the right side, <math>{\sigma}/{E}\,</math>, is equal to the elastic part of the strain, while the second term, <math>\ K({\sigma}/{E})^n</math>, accounts for the plastic part, the parameters <math>K</math> and <math>n</math> describing the ''hardening behavior'' of the material. Introducing the ''yield strength'' of the material, <math>\sigma_0</math>, and defining a new parameter, <math>\alpha</math>, related to <math>K</math> as <math>\alpha = K ({\sigma_0}/{E})^{n-1}\,</math>, it is convenient to rewrite the term on the extreme right side as follows: | |||

::: <math>\ K \left(\frac{\sigma}{E} \right)^n = \alpha \frac{\sigma_0}{E} \left(\frac{\sigma}{\sigma_0} \right)^n</math> | |||

Replacing in the first expression, the Ramberg–Osgood equation can be written as | |||

::: <math>\epsilon = \frac{\sigma}{E} + \alpha \frac{\sigma_0}{E} \left(\frac{\sigma}{\sigma_0} \right)^n</math> | |||

==Hardening behavior and yield offset== | |||

In the last form of the Ramberg–Osgood model, the ''hardening behavior'' of the material depends on the material constants <math>\alpha\,</math> and <math>n\,</math>. Due to the [[power law|power-law]] relationship between stress and plastic strain, the Ramberg–Osgood model implies that plastic strain is present even for very low levels of stress. Nevertheless, for low applied stresses and for the commonly used values of the material constants <math>\alpha</math> and <math>n</math>, the plastic strain remains negligible compared to the elastic strain. On the other hand, for stress levels higher than <math>\sigma_0</math>, plastic strain becomes progressively larger than elastic strain. | |||

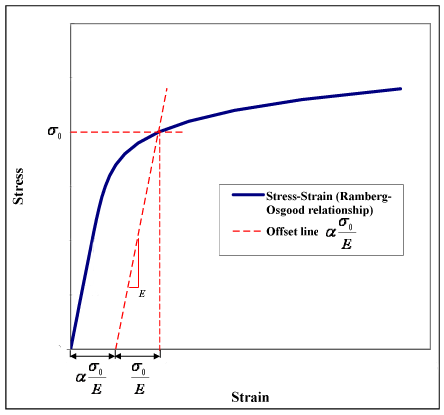

The value <math>\alpha \frac{\sigma_0}{E}</math> can be seen as a ''yield offset'', as shown in figure 1. This comes from the fact that <math>\epsilon = (1+\alpha){{\sigma_0}/{E}}\,</math>, when <math>\sigma = \sigma_0\,</math>. | |||

Accordingly (see Figure 1): | |||

: ''elastic strain at yield'' = <math>{{\sigma_0}/{E}}\,</math> | |||

: ''plastic strain at yield'' = <math>\alpha({\sigma_0}/E)\,</math> = ''yield offset'' | |||

Commonly used values for <math>n\,</math> are ~5 or greater, although more precise values are usually obtained by fitting of tensile (or compressive) experimental data. Values for <math>\alpha\,</math> can also be found by means of fitting to experimental data, although for some materials, it can be fixed in order to have the ''yield offset'' equal to the accepted value of strain of 0.2%, which means: | |||

::: <math>\alpha \frac{\sigma_0}{E} = 0,002</math> | |||

[[Image:Ramberg-osgood-2.png|frame|none|'''Figure 1''': Generic representation of the Stress-Strain curve by means of the Ramberg–Osgood equation. Strain corresponding to the yield point is the sum of the elastic and plastic components.]] | |||

==References== | |||

<references/> | |||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ramberg-Osgood relationship}} | |||

[[Category:Mechanics]] | |||

[[Category:Materials science]] | |||

Revision as of 13:35, 27 May 2013

The Ramberg–Osgood equation was created to describe the non linear relationship between stress and strain—that is, the stress–strain curve—in materials near their yield points. It is especially useful for metals that harden with plastic deformation (see strain hardening), showing a smooth elastic-plastic transition.

In its original form, the equation for strain (deformation) is[1]

where

- is strain,

- is stress,

- is Young's modulus, and

- and are constants that depend on the material being considered.

The first term on the right side, , is equal to the elastic part of the strain, while the second term, , accounts for the plastic part, the parameters and describing the hardening behavior of the material. Introducing the yield strength of the material, , and defining a new parameter, , related to as , it is convenient to rewrite the term on the extreme right side as follows:

Replacing in the first expression, the Ramberg–Osgood equation can be written as

Hardening behavior and yield offset

In the last form of the Ramberg–Osgood model, the hardening behavior of the material depends on the material constants and . Due to the power-law relationship between stress and plastic strain, the Ramberg–Osgood model implies that plastic strain is present even for very low levels of stress. Nevertheless, for low applied stresses and for the commonly used values of the material constants and , the plastic strain remains negligible compared to the elastic strain. On the other hand, for stress levels higher than , plastic strain becomes progressively larger than elastic strain.

The value can be seen as a yield offset, as shown in figure 1. This comes from the fact that , when .

Accordingly (see Figure 1):

Commonly used values for are ~5 or greater, although more precise values are usually obtained by fitting of tensile (or compressive) experimental data. Values for can also be found by means of fitting to experimental data, although for some materials, it can be fixed in order to have the yield offset equal to the accepted value of strain of 0.2%, which means: