The Kolsky basic model and modified model for attenuation and dispersion

Hard magnet is the magic material used to make the compass. Its ability to build up static magnetic field finds the applications from refrigerator sticker to electric motor. In pursuit of strong hard magnet, the magnetic material containing rare earth elements, such as neodymium iron boron and samarium cobalt magnet has been invented. Neodymium iron boron magnet is the strongest one, which has a theoretical maximum energy product of 512 kJ/m3 and the magnet with 92% of this value has already been produced. Around 1990, a group of Soviet researchers led by Nikolay Manakov, and independently, Eckart Kneller and Reinhard Hawig in Germany proposed approaches to make so-called exchange spring magnet which comprises two phases of magnetic materials, one having high coercivity and one having high saturation magnetization [1].

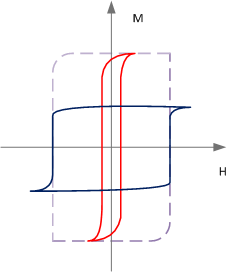

The commercial neodymium iron boron magnets have the coercivity of 1000-2000 kA/m, and the remanent magnetization is 1.2-1.4 T. But for a soft magnetic material, such as iron cobalt alloy, the saturation magnetization can achieve 2.4 T. The exchange spring magnet takes the advantage of the soft magnetic material and obtain the high energy density. For a simple illustration, by incorporating soft phase and hard phase magnetic material, whose hystersis loops are shown as red and blue curves, the ideal hystersis loop of exchange spring magnet can be expressed as the loop with the dashed line.

Another benefit of exchange spring magnet is that the volume fraction of the hard phase material can be made lower than 10% and the rest volume is made of soft magnetic material. Since the cost and short supply of the rare earth elements boosts up the price of the high-performance hard magnet and the price of soft magnetic materials is relatively low, the exchange spring magnet may obtain great properties with low cost.

Principle

Magnetic energy

The magnetic moment of bulk material is the sum of all the atomic moments inside. The interaction of these atomic moments among themselves and with the externally applied field determines the magnetic behavior of the magnet. In the perspective of energy, each atomic magnetic moment tries to orient in the way that the magnetic energy settles down to a minimum. There are generally four types of energy competing with each other to reach an equilibrium. Each of them comes from the exchange coupling effect, magnetic anisotropy, and the magnetiostatic energy of the magnet itself and its interaction with external field. As shown in the figure below, the magnetic moment of a small group of atoms is expressed by an arrow.

The exchange coupling is a quantum mechanical effect that keep the adjacent moment aligned with each other. The exchange energy increases if there is an angle difference between the adjacent moments.

The magnetic anisotropy energy comes from the crystalline structure of the material. For a simple case, the effect can be modeled by an uniaxial energy distribution. Along an axial direction, so-called easy axis, the magnetic moments tend to align. The energy rises if the orientation of magnetic moment deviates from the easy axis.

The magnetostatic energy is the energy stored in the magnetic field generated by the magnetic moments. The magnetic field reaches its maximum intensity if all the magnetic moments orient to one direction that is what happens to the hard magnet. In order to prevent building up the magnetic field, the magnetic moments tend to form loops. In that way, the energy stored in the magnetic field can be constrained and that is what occurs inside the soft magnet. What determines a magnet to be soft or hard is the dominant term of magnetic energy. For hard magnet, the anisotropy constant is fairly large that makes magnetic moments aligned with easy axis and generates the field. The opposite case applies to soft magnet, the magnetostatic energy is dominant.

Another magnetostatic energy is caused by the interaction with external field. The magnetic moments try to point at the direction of applied field.

Since the magnetostatic energy dominates in soft magnet, the tendency for magnetic moments to follow the external field makes it soft.

Exchange spring magnet

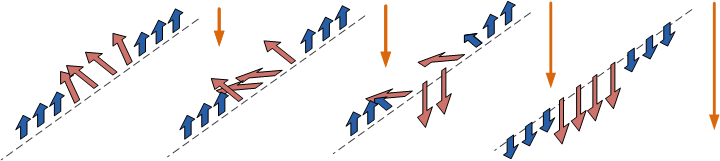

In the exchange spring magnet, there are the hard phase with high coercivity and the soft phase with high saturation field. The hard phase and the soft phase interact through their interface by exchange coupling. Assume a one-dimensional case of the interface as shown in the figure, where the blue arrows stand for the magnetic moments in the hard phase and the red arrows stand for those in soft phase. The length of the arrow shows the magnetization and the width shows the coercivity. The easy axis is assumed to be in the vertical direction.

From the left to right in figure, an external field is first applied upward to saturate the magnet. Then the external field is reversed and starts to demagnetize the magnet. Since the coercivity of hard phase is pretty high, the moments remains unchanged to minimize the anisotropy and exchange energy. The magnetic moments in soft phase starts rotating to align the moments with the applied field [2]. Because of the exchange coupling through the interface, the magnetic moment at the soft phase boundary has to align with the moment in hard phase. At the region close to the interface, because of the exchange coupling, the chain of magnetic moments act as a spring. If the external field is increased, the more moments in soft phase rotates downward and the width of transition region becomes smaller where the exchange energy density gets increased. But the magnetic moments in hard phase do not rotate, until the external field is high enough that the exchange energy density i the transition is comparable to the anisotropy energy density in the hard phase. Then the rotation of magnetic moments inside soft phase start to affect the hard phase. As the reversed external field surpasses the hard coercivity, the hard magnet gets fully demagnetized.

In previous process, when the magnetic moments in the hard magnet start to rotate, the intensity of external field is already much higher than the coercivity of soft phase, and there is still a transition region in soft phase. If the thickness of soft phase is made less than twice as thick as the transition region, this soft phase would have a large effective coercivity, though it should smaller than the coercivity in hard phase but they are comparable.

This time in the case of thin soft phase, it is hard for the external field to rotate the magnetic moments in the soft phase which acts just like hard magnet with high saturation magnetization. More interesting, after applying a high external field to partially demagnetize the magnetic moments in hard phase and then removing the external field, the rotated moments in soft phase can be pulled back by the exchange coupling to align with the moments in hard phase. This phenomenon is shown in the hysteresis loop of exchange spring magnet.

Compare the hysteresis loop with a conventional hard magnet and the two-phase magnet without interaction, the exchange spring magnet is more likely recover from the opposite external field. When the external field is removed, the remanent magnetization can recover to the degree that is close to its original value. The name of exchange spring magnet is granted for the reversibility of magnetization [3].

The dimension of the soft phase inside the exchange spring magnet should be kept small enough to let the mentioned effect happen. In the meanwhile, the volume fraction of soft phase should be made as large as possible to get the high saturation magnetization. One good solution is to fabricate the magnet which has the structure of embedding hard phase particles inside soft phase matrix. In the way, the matrix material occupies the large portion of volume and also close to the hard phase particles. The dimension of and the spacing among the hard phase particles is in the scale of nanometer. If the hard magnetic are spheres on an fcc space lattice in soft magnetic phase, the volume fraction of hard phase is 9% and then 91% soft phase. Since the total saturation magnetization is summed up by the volume fraction, it is close to value of pure soft phase.

Fabrication

The fabrication of the exchange spring magnet is not easy thing, which requires the precise control of the particle-matrix structure and nanometer-scale dimension. Kinds of approaches have been tested, such as metallurgical method, sputtering, particle self-assembly, etc.

- Particle self-assembly. 4 nm Fe3O4 nanoparticles and 4 nm Fe58Pt42 nanoparticles dispersed in solution were deposited as compact structures through self-assembly by evaporating the solution. Then through annealing, FePt-FePt3 nanocomposite magnet was formed. The energy density has been increased from 117 kJ/m3 of the single phase Fe58Pt42 to 160 kJ/m3 of FePt-FePt3 nanocomposite [4].

- Sputtering. In the process, a layer of separate sputtering-based air phase FePt nanoparticles was deposited and then another layer of FeNi thin film was sputtered. By repeating these steps, the particle-matrix structure was achieved and it showed an energy density of 118 kJ/m3 [5].

Reference

- [1] Template:Brokenlinkhttp://spectrum.ieee.org/semiconductors/nanotechnology/the-incredible-pull-of-nanocomposite-magnets/1gy/the-incredible-pull-of-nanocomposite-magnets/1

- [2] P. M. S. Monteiro and D. S. Schmool, Phys. Rev. B 81, 214439 (2010)

- [3] Eckart F. Kneller. and Reinhard Hawig, IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, Vol. 27, No. 4, 1991

- [4] Hao Zeng, Jing Li, J. P. Liu, Zhong L. Wang Shouheng Sun, Nature, Vol 420, 2002

- [5] Xiaoqi Liu, Shihai He, Jiao-Ming Qiu, and Jian-Ping Wanga, Applied Physics Letters 98, 222507, 2011